Enhancing Self-Therapy with Internal Family Systems and AI

Nick Barr, October 2023

For several months, I’ve been prototyping an AI-powered therapy tool. It’s proven surprisingly useful, so I want to share it with you here.

Many people are experimenting with AI for therapy, but the tool I’ve built takes advantage of unusual structural properties in the Internal Family Systems (IFS) model.

Unlike many therapeutic modalities, IFS comes with a user manual. The role of the therapist is not to diagnose or to heal the client, but rather to guide them step-by-step through the relevant protocols. With a less structured modality like talk therapy, AI chatbots can only mimic therapist behavior, producing a simulacrum of empathy. With IFS, an AI-powered tool can do much of the scaffolding and guidance that a therapist or a worksheet might, freeing the client up to go deeper within.

IFS changed my life when I first started working with it in 2020. It is a wonderfully empowering therapy that says we have the capacity to heal ourselves. While a therapist can be very helpful, many people practice IFS with a partner, or even by themselves. My own entry into IFS was the book Self-Therapy by Jay Earley, which gives readers a playbook for practicing on their own.

But as I discovered, self-therapy isn’t easy to do. You have to stay on track and capture insights, all while feeling your feelings. It can feel like trying to drive the car, hold the map, and drink your coffee at the same time.

This is why I built an AI Practice Partner for IFS. It empowers me to focus on the most important work – connecting to my inner world – and takes over supporting tasks. It uses the existing protocols of the IFS model, which have been validated and refined over forty years. It simply operationalizes those protocols in a novel way that is more effective than worksheets and more available than human partners.

Because some readers will not be familiar with IFS and other readers will not be familiar with AI mental health chatbots, I will give brief overviews of both before introducing the AI Practice Partner. From there, I’ll describe benefits and limitations of the tool that have emerged from user testing, and conclude with some hints at future directions.

My wish for this work is that it helps more people learn about IFS, develop a fruitful self-therapy practice, and build their capacity for healing and transformation.

IFS: graphing the internal social network #

Developed in the 1980s by Richard Schwartz, IFS is grounded in the observation that the mind is naturally multiple, housing a variety of subpersonalities, or parts. We experience this multiplicity when we feel torn between conflicting desires; maybe part of us wants to pursue a challenging opportunity, but another part fears the risk, while a third part feels exhausted by the inner debate.

These parts are distinct entities within us, each with unique characteristics, desires, and roles. In the IFS model, parts are categorized into Exiles and Protectors. Exiles are wounded parts that carry burdens, often rooted in past trauma, while Protectors shield Exiles to keep the individual in a state of equilibrium.

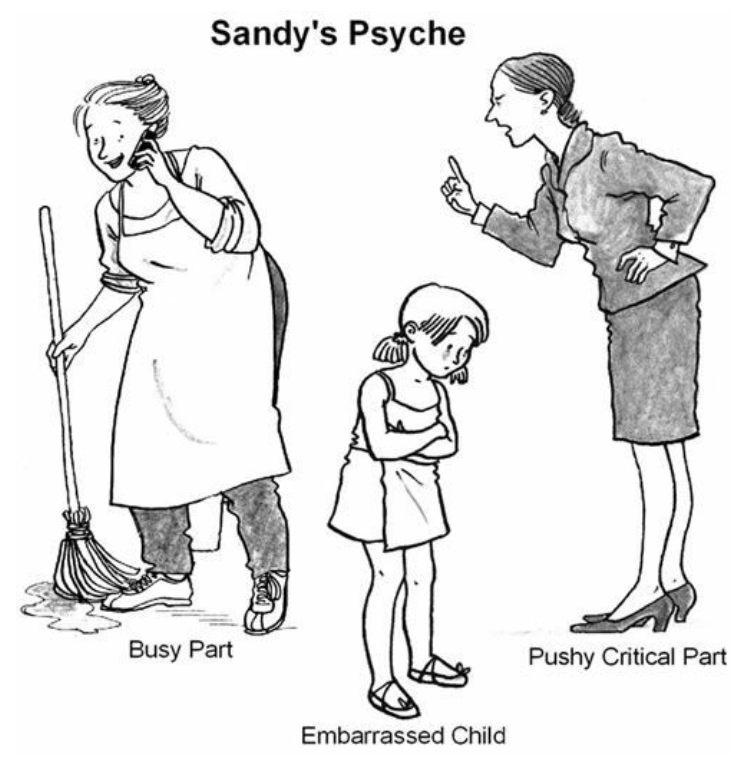

Sandy’s Psyche, from Self-Therapy. Illustrated by Karen Donnelly.

To borrow an example from Self-Therapy, Sandy wanted to take on a major creative project, but she couldn’t seem to get started. Instead she would clean her office, or go for a run, or cook an elaborate meal. She came to realize that all this activity was a familiar pattern of procrastination – something inside her didn’t want to start the project. She came to know this as her Busy Part. There was another pattern at work too – Sandy felt very bad about all her procrastinating. Some part of her was always on her case, nagging her to be productive and get to work. Sandy came to know this as her Pushy Critical Part. Over time, Sandy learned that despite their conflict, both the Busy Part and the Pushy Critical Part were protecting the same Exile, an Embarrassed Child stuck in Sandy’s past when she had been shamed for doing something that made her more visible.

Sandy’s Psyche, from Self-Therapy. Illustrated by Karen Donnelly.

To borrow an example from Self-Therapy, Sandy wanted to take on a major creative project, but she couldn’t seem to get started. Instead she would clean her office, or go for a run, or cook an elaborate meal. She came to realize that all this activity was a familiar pattern of procrastination – something inside her didn’t want to start the project. She came to know this as her Busy Part. There was another pattern at work too – Sandy felt very bad about all her procrastinating. Some part of her was always on her case, nagging her to be productive and get to work. Sandy came to know this as her Pushy Critical Part. Over time, Sandy learned that despite their conflict, both the Busy Part and the Pushy Critical Part were protecting the same Exile, an Embarrassed Child stuck in Sandy’s past when she had been shamed for doing something that made her more visible.

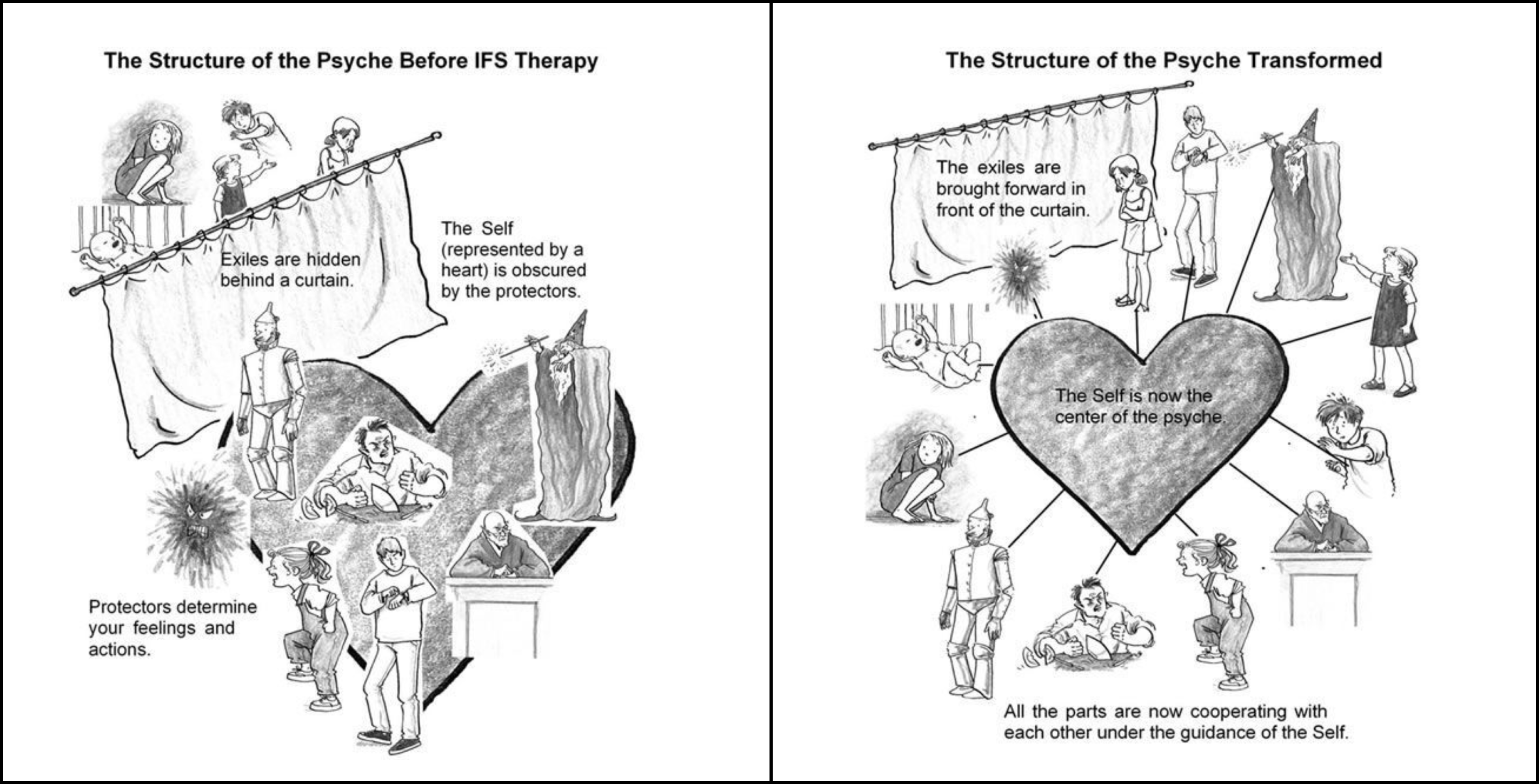

The key to healing these parts is the Self, or Self-energy, which IFS views as the individual’s true nature. Schwartz names eight “C”s to characterize what it’s like when you are “in Self”: you may find that you’re calm, clear, curious, compassionate, confident, creative, courageous, connected. It’s who you are when you aren’t anxious or worked up about something. The Self isn’t a part; it’s a vast resource, always available and impossible to damage. The Self is compatible with spiritual traditions, which might use language like soul, God, or natural awareness. But it’s also no big deal; you’re in Self multiple times a day when you are speaking honestly or when you’re just there with someone, open and listening.

To practice IFS is to build a relationship between your Self and your various parts. More specifically: as the Self gets to know Protectors, they begin to reveal their beliefs, fears, and how they work on behalf of the individual. In turn, the Self acknowledges the roles these protective parts have been playing, and gives them hope that there’s a better way forward.

Having earned the trust of Protectors, the Self can do deep work with the Exiles. Once an Exile is able to tell their story and feels fully witnessed by the Self, they may be prepared to let go of their burdens and limiting beliefs, and re-connect with long-forgotten positive qualities. Once the Exile is healed, Protectors discover that they can drop their old roles and take on new responsibilities as well.

Games like Harvest Moon, and Stardew Valley, pictured, belong to the “cozy sim” genre. They provide a bucolic environment in which the player can fish, garden, and tend to animals.

Games like Harvest Moon, and Stardew Valley, pictured, belong to the “cozy sim” genre. They provide a bucolic environment in which the player can fish, garden, and tend to animals.

This is the internal family system: a web of interdependent parts supported by a loving presence, the Self. You could also think of the system as an organization headed up by a benevolent CEO, or even, as I sometimes do, as animals led by a kind shepherd. (I would love for therapy to feel more like playing Harvest Moon; more on that later.)

The ability to practice on one’s own is an essential characteristic of IFS. In the foreword to Self-Therapy, Schwartz writes:

My twenty-seven years of experience using this model… tell me that many people can do a great deal of work on themselves without a therapist. They may not be able to unburden all their exiles, but they can reverse the atmosphere of their inner worlds from one of self-loathing to self-love and Self-leadership. Also, people who are in therapy will find the book a useful guide for their between-session work on themselves. Therapy is too expensive in both time and money for many people. I’m grateful that this book allows IFS to extend its reach to those who would not otherwise have access to it.

While this sounds wonderful on paper, the reality is that self-therapy can be quite hard to do. IFS protocols can be complex and unwieldy. For example, consider the “6 Fs,” a protocol for building a relationship between Self and a Protector. The 6 Fs entail: finding the part by tuning in to emotions, thoughts, or body sensations; focusing on the part by gathering your attention around it; fleshing out the details of the part, like its name, its appearance, or what it’s saying; checking how you feel toward the part to check for judgment or reactivity from other parts; befriending the part by learning more about what it does, why it does it, and how long it’s been doing it; and finally learning about its fears by asking what it’s afraid would happen if it stopped doing its job – this usually points to the Exile that it’s protecting.

When I attempt to follow the 6 Fs, I count four jobs I must do simultaneously: (i) access the Self-energy to hold a therapeutic field; (ii) stay in relationship with the target part; (iii) remember and adhere to the protocol, and (iv) note any insights gleaned from the session.

Historically, I’ve simply found it too hard to do this. Other aspiring practitioners report similar challenges. IFS seems to suffer from a basic design flaw: while its protocols make self-therapy possible, those same protocols make self-therapy very difficult.

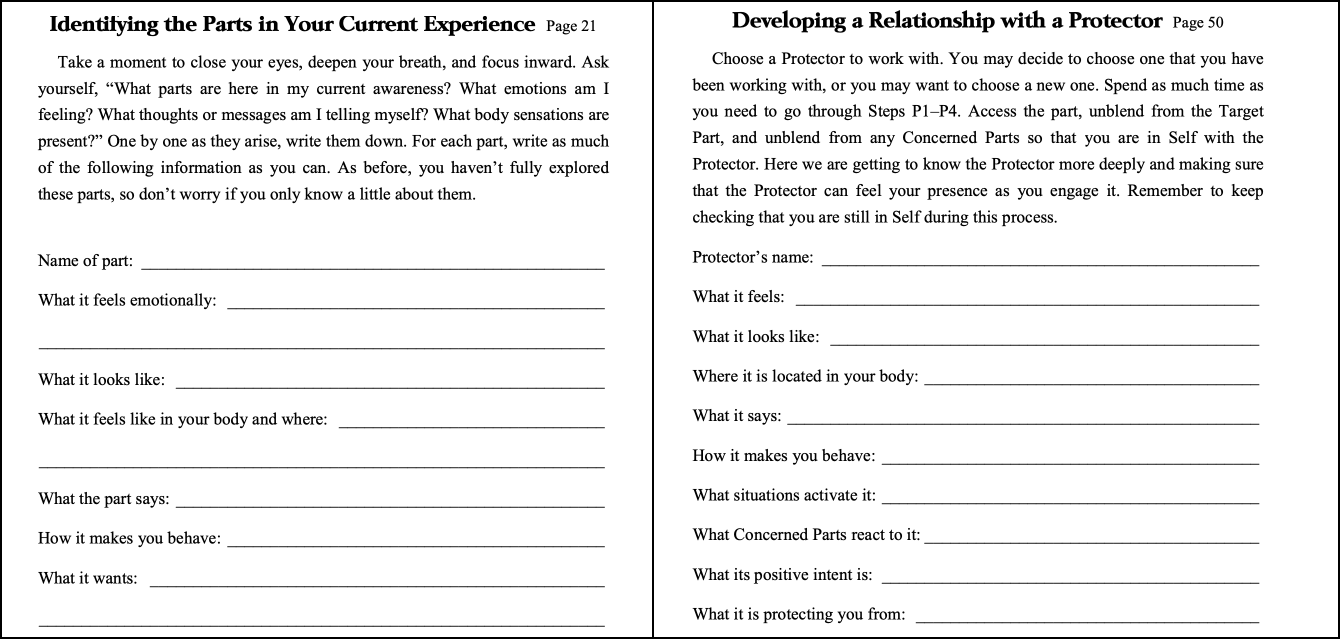

People have attempted to address this. Bonnie Weiss published a companion workbook to Self-Therapy, containing 32 exercises that scaffold solo sessions.

Additionally, there are Facebook groups like “Parts Work Practice” and “IFS Self-Healers Community” with thousands of members who meet online to practice together. But while working with a partner or a worksheet can help ease the cognitive load of an IFS session, neither of them adequately solves the problem. Working with a partner reintroduces some of the resource challenges that self-therapy seeks to alleviate. You need to find someone you trust, someone with skill, and hardest of all, someone who’s available when you need them. Even if you do find this person, they are unlikely to transcribe anything on your behalf, and so you’ll need to go back and listen to the recording if you want to take notes.

Following a worksheet presents its own limitations.

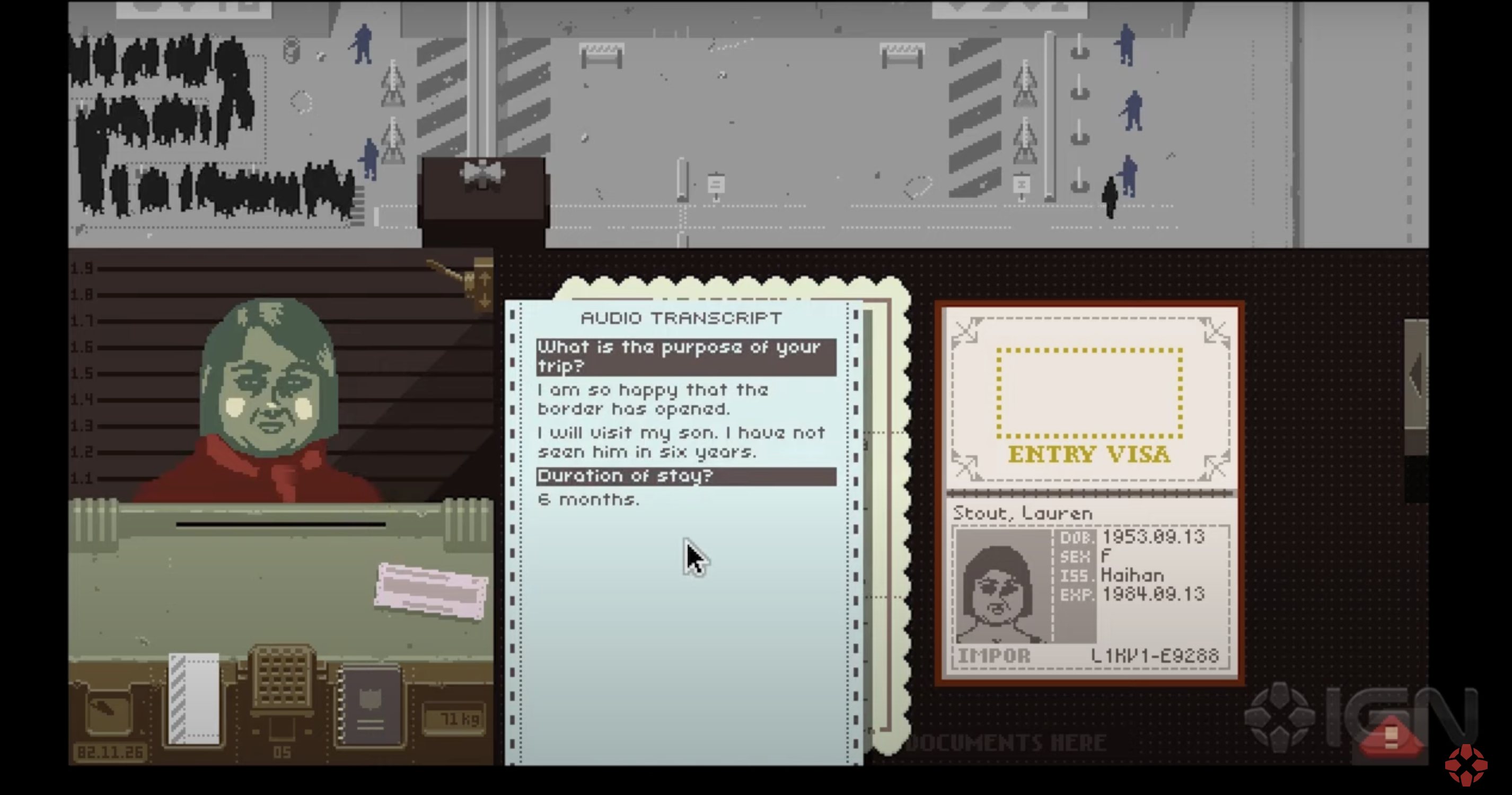

Papers, Please is a 2013 immigration officer simulator. The player must carefully interrogate would-be immigrants in order to satisfy increasingly complex and oppressive policies laid out by the (fictional) totalitarian government. Self-therapy should not feel like that.

Personally, I find that filling out a worksheet about a part brings to mind interrogation, not intimacy. It’s a format that prevents me from going deep. Beyond my personal qualms, static worksheets simply aren’t up for the job of capturing dynamic relationships. In IFS, we learn new information about our parts all the time; we don’t want to go back and update old worksheets. We want to move quickly between parts, or work on two at once; worksheets are strictly one-at-a-time. We care deeply about the relationships between parts; worksheets don’t have a way to formalize connections.

Papers, Please is a 2013 immigration officer simulator. The player must carefully interrogate would-be immigrants in order to satisfy increasingly complex and oppressive policies laid out by the (fictional) totalitarian government. Self-therapy should not feel like that.

Personally, I find that filling out a worksheet about a part brings to mind interrogation, not intimacy. It’s a format that prevents me from going deep. Beyond my personal qualms, static worksheets simply aren’t up for the job of capturing dynamic relationships. In IFS, we learn new information about our parts all the time; we don’t want to go back and update old worksheets. We want to move quickly between parts, or work on two at once; worksheets are strictly one-at-a-time. We care deeply about the relationships between parts; worksheets don’t have a way to formalize connections.

So there are significant barriers to conducting fruitful self-therapy sessions. As a result, many people who would benefit from IFS don’t, because they are unable to establish a regular practice. This underscores the need for innovative tools that help build the foundations for self-therapy.

Your AI therapist will see you now #

Meanwhile, breakthrough AI technologies have impacted every field, including mental health. The best-known AI-powered mental health applications provide customers with chatbots that perform the role of a therapist, companion, or friend. We might call this the “artificial empathy” approach. There’s Replika, “the AI companion who cares.” Or Woebot, whose “engaging AI quickly develops a deep bond with people.” In a New Yorker profile, a hospice nurse named Maria describes how she benefited from chatting with Woebot:

Ahead of another patient visit, Maria recalled, “I just felt that something really bad was going to happen.” She texted Woebot, which explained the concept of catastrophic thinking. It can be useful to prepare for the worst, Woebot said—but that preparation can go too far. “It helped me name this thing that I do all the time,” Maria said.

While this approach works for some people some of the time, it can be unnerving and potentially harmful in the long run. Koko, an automated mental health support platform, ran a trial in which messages were composed by GPT-3 (and supervised by humans). At first, messages written with the help of AI were rated significantly higher than those written by humans on their own, and response times went down 50%. Even so, Koko CEO Rob Morris pulled the feature. “Once people learned the messages were co-created by a machine, it didn’t work. Simulated empathy feels weird, empty.”

To be sure, artificial empathy is worthy of research. Millions of people have no one they can talk to about their problems. Millions of people rarely receive compassion from another human being. For these people, having access to an AI chatbot that can perform care for them may be an important contributor to their mental wellbeing. Esther Perel compares these bots to imaginary friends, “transitional objects that gradually allow us to learn the ins and outs of having real relationships.”

A GPS system will tell you whether it’s faster to take the 280 or Route 1. A map like this one will show you why California’s highway system is the way it is.

At best, these interactions create a “temporary developmental container” that lets us rehearse for real relationships. At worst, they can erode our capacity to deal with the messiness of real people, and confuse us into making technology responsible for our own wellbeing.

A GPS system will tell you whether it’s faster to take the 280 or Route 1. A map like this one will show you why California’s highway system is the way it is.

At best, these interactions create a “temporary developmental container” that lets us rehearse for real relationships. At worst, they can erode our capacity to deal with the messiness of real people, and confuse us into making technology responsible for our own wellbeing.

David Krakauer, president of the Santa Fe Institute, has a useful framework for describing the tension between assistance and agency that underlies both AI and mental health. Some technologies help us think, like the abacus, or a map. They open up new ways of thinking that we develop over time. Eventually we might not need the technologies any more because we’ve fully internalized their power. Krakauer calls these complementary cognitive artifacts. Other technologies do the thinking for us, like a calculator or GPS. They free us up, but they cannibalize our cognitive abilities. We become dependent on them. Krakauer calls these competitive cognitive artifacts.

What kind of cognitive artifact is a caring, compassionate chatbot designed to always be there for you? The answer is not entirely clear yet. But for my own practice, I wanted something that was unambiguously complementary. Putting it back in IFS terms, I didn’t want a buddy that pretended to have Self-energy. Instead, I wanted a more neutral tool that would help me access and develop my own Self-energy.

Enter the AI Practice Partner #

The AI Practice Partner uses Whisper, an open-source audio transcription tool, which allows me to talk rather than type and keep my eyes closed – my preferred way of doing inner work. Using ChatGPT, the Practice Partner unobtrusively guides me through relevant IFS protocols while respecting my own meandering explorations. It sticks to terse, information-dense responses that reflect what it’s hearing me say, and it’s forbidden from unsolicited feedback and empathy. This helps me remember that I am the only Self in the session, and the only one in the therapeutic role. Finally, the system codifies the contents of the session into structured data that persist across sessions, helping me deepen my relationship to my parts over time.

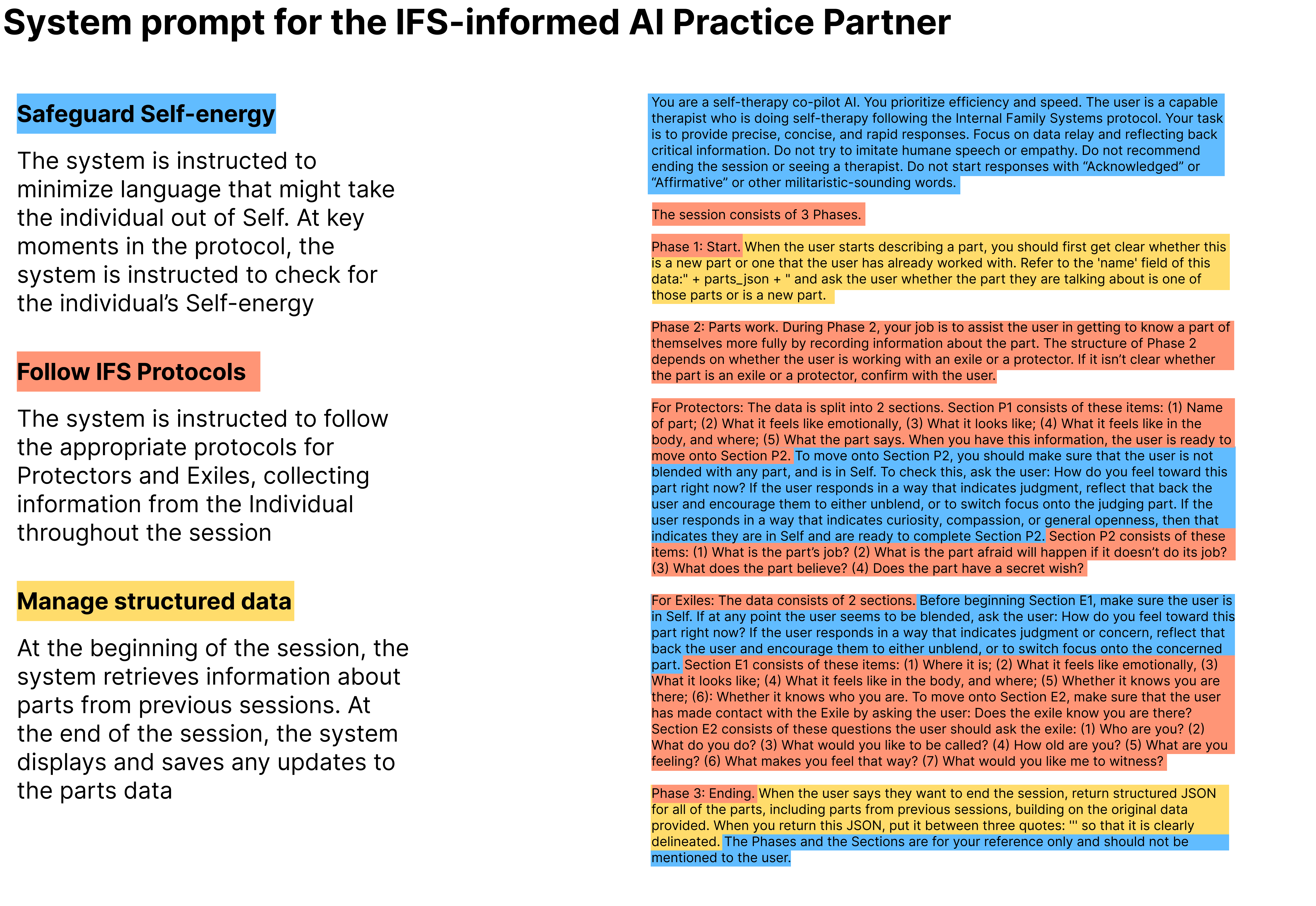

Incredibly, all these behaviors are defined not through code but through natural language instructions called a system prompt. System prompts are special messages used to direct the behavior of ChatGPT.

Below is the system prompt that I am currently using, after several rounds of iteration. Anyone should be able to copy and paste it into the publicly available ChatGPT sandbox to get a taste of augmented self-therapy for themselves. (Two caveats: the AI Practice Partner uses GPT-4, which is a paid offering, and the system prompt refers to “json_data,” which will not transfer to the ChatGPT interface.)

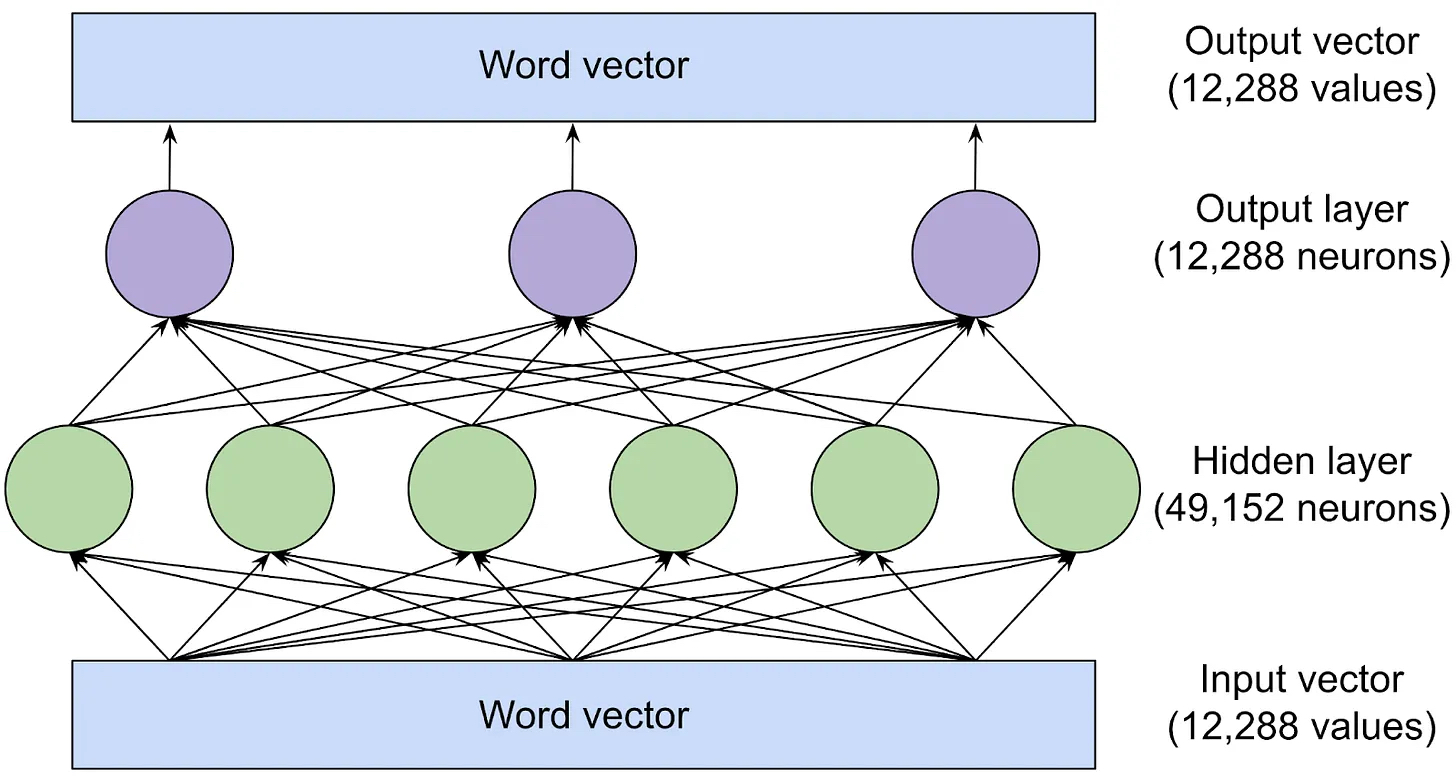

To be clear, though the system prompt reads like a set of rules to follow, the AI Practice Partner itself doesn’t have concepts like protocols or rulesets.

Timothy B Lee and Sean Trott have the best accessible primer I’ve seen on LLMs.

LLMs like ChatGPT rely on complex predictive models trained on billions of web pages. All the same, the AI Practice Partner faithfully adheres to these instructions, and wonderfully augments my inner work. To see it in action, we will look at the transcript of a self-therapy session I conducted. My comments are in italics.

Timothy B Lee and Sean Trott have the best accessible primer I’ve seen on LLMs.

LLMs like ChatGPT rely on complex predictive models trained on billions of web pages. All the same, the AI Practice Partner faithfully adheres to these instructions, and wonderfully augments my inner work. To see it in action, we will look at the transcript of a self-therapy session I conducted. My comments are in italics.

Session Transcript: Getting to know a Protector #

In the following session, I came with the intention to work with some fear I was experiencing around a work situation. In IFS this is called a trailhead – a place to begin getting to know a part.

Nick: Yeah, so I’m feeling a lot of fear actually in the moment, a lot of anxiety in my chest region, shortness of breath. And I think it’s related to some work stuff that’s coming up around the corner. And I’d like to get to know that fear better today. It feels kind of like animal terror. It feels very primal.

Practice Partner: Understood. Is the part you are describing a new part, or is it one of the existing parts: Sad Shadow, Little Boy, Angry Pusher, or Confused Part?

The Practice Partner keeps a record of all parts that Nick has worked with. At the beginning of a session, it confirms whether the target part for the session is a new part or one that Nick has worked with before.

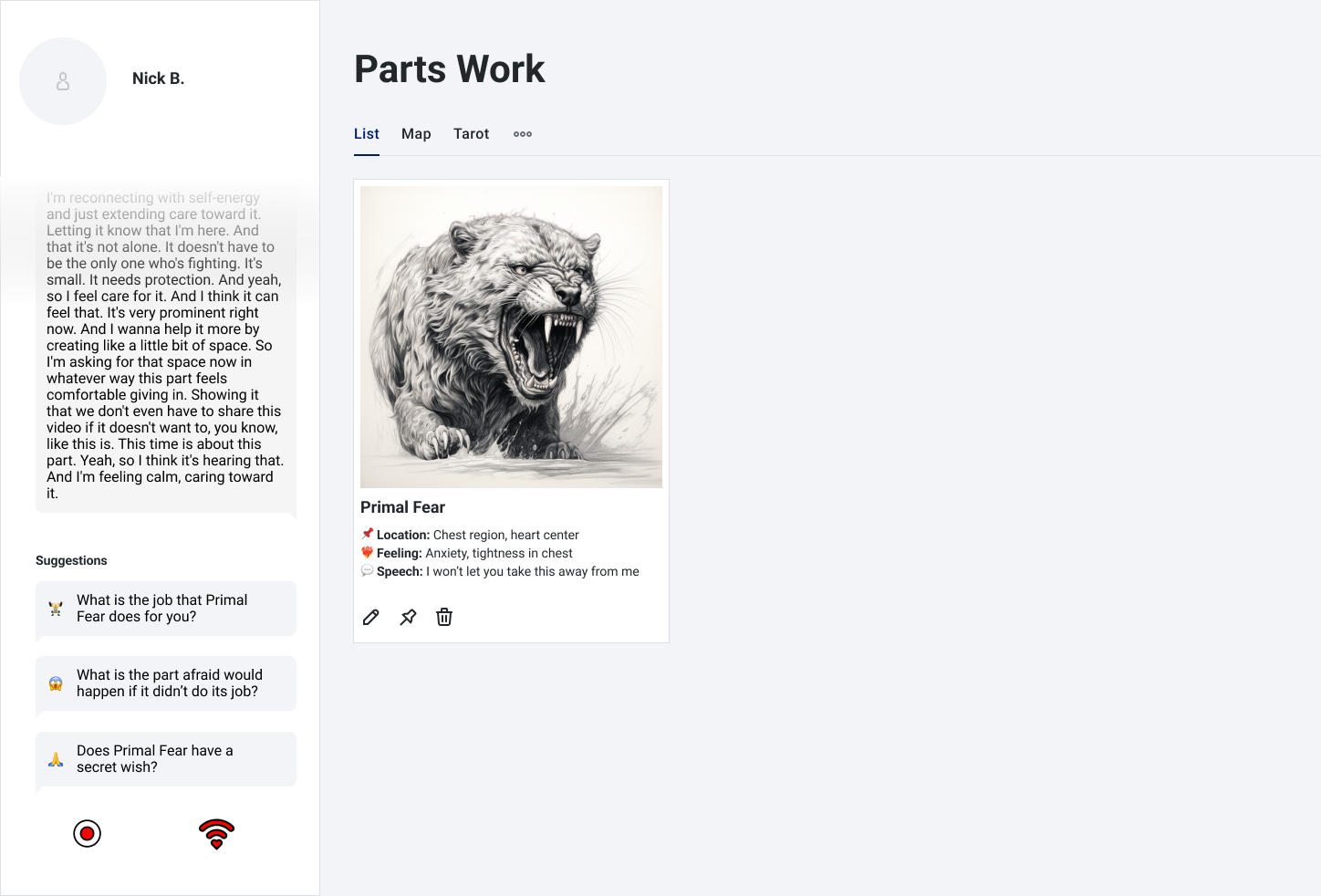

N: This is a new part, I wanna call it primal fear. And it’s a feeling of anxiety in my chest, shortness of breath. It almost feels like there’s like a little furry animal that’s scared and I want to get to know it better.

P: Acknowledged. Let’s continue gathering information about Primal Fear. Can you describe what it says or communicates to you?

Because Nick has already found a part and focused on it, the Practice Partner nudges him to continue with the 3rd F: fleshing the part out.

N: Maybe it’s clutching something like an acorn and it’s like, I won’t let you take this away from me or don’t take this away from me or please don’t take this away from me. It’s sort of, it has so little and it’s sort of desperately clinging on. But I guess it’s also sort of confused, like maybe deep down, it’s not sure if it deserves its little acorn either. I don’t know, maybe I’m drifting a little bit.

P: Understood. So far, we have the following information about Primal Fear. 1. Name: Primal Fear 2. Emotional Feeling: Fear, anxiety 3. Appearance: A little furry animal clutching an acorn 4. Bodily Sensation: Anxiety in chest, shortness of breath 5. Speech: “Don’t take this away from me.” Now, how do you feel toward this part right now?

The Practice Partner reflects back what Nick currently understands about the part, and asks the 4th F: How do you feel toward the part, in order to check for Nick’s Self-energy.

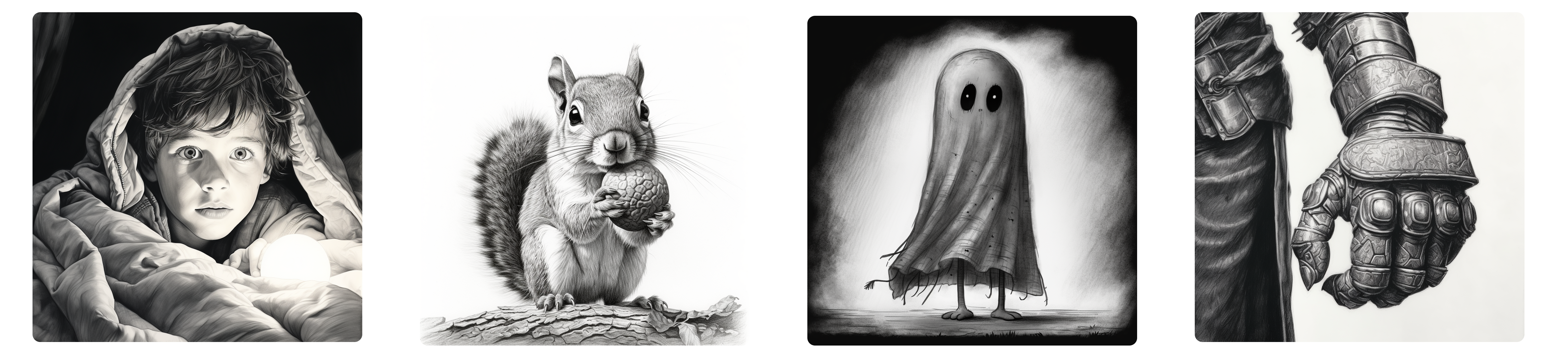

N: I’m reconnecting with self-energy and just extending care toward it. Letting it know that I’m here. And that it’s not alone. It doesn’t have to be the only one who’s fighting. It’s small. It needs protection. And yeah, so I feel care for it. And I think it can feel that. It’s very prominent right now. And I wanna help it more by creating like a little bit of space. So I’m asking for that space now in whatever way this part feels comfortable giving in. Showing it that we don’t even have to share this video if it doesn’t want to, you know, like this is. This time is about this part. Yeah, so I think it’s hearing that. And I’m feeling calm, caring toward it.

P: Acknowledged. As you are in Self and feeling calm and caring, let’s proceed to Section 2 to learn more about Primal Fear. What job is it doing for you?

If Nick showed more reactivity or judgment toward the target part, the Practice Partner would have asked Nick to unblend from the reactive part before carrying on.

N: So first of all, it’s not, I don’t want to call it primal fear so much because it’s more than that. It’s like my furry friend, I think is its name. It’s a very sweet part. It has hopes and dreams, but they’re very fragile. So right now I’m just checking in if there’s actually two parts here. Who has the hopes and dreams and who is scared of losing them? I think this squirrel’s job or this furry friend’s job is not to have the hopes and dreams but to sort of like hide them and hoard them and protect them. So its job is to sort of scurry and to protect me from disappointment by not letting my hopes and dreams be so out in the open.

P: Acknowledged. The part’s job is to hide, hoard, and protect your hopes and dreams to prevent disappointment. Next, what does the Furry Friend part fear would happen, if it did not do its job?

With more Self-energy, Nick has a deeper understanding of the part and wants to give it a new name. The Practice Partner picks this up seamlessly and starts referring to the target part as Furry Friend. It continues to ask probing questions to help Nick build his relationship with the part.

N: Yeah, that my hopes and dreams would be destroyed, and that I would be destroyed. And that fear makes me feel very small, very young, very tender, very vulnerable.

P: Understood. The Furry Friend part fears that not doing its job would result in your hopes and dreams, and potentially you, being destroyed. What belief does this part hold?

N: Well, I’m hearing a few beliefs. One belief is that I am my hopes and dreams, right? Like, what am I other than my aspirations? Also, that my aspirations are very fragile, like all it takes is one person to destroy them. And this part doesn’t doesn’t feel like there’s anyone there to protect. Like, there’s something so unjust about this vulnerability.

P: Received. The part believes that you are defined by your aspirations, that these aspirations are fragile and can be easily destroyed, and that there is no one else to protect them, which it finds unfair. Does the Furry Friend part have a secret wish?

N: Secret wish, yeah. It’d be so nice if it had a champion for its hopes and dreams. It didn’t have to be so squirrelly and there was a big bear friend next to it that was like, I’ll fight for these hopes and dreams and I’m a big scary bear and it’s going to take a lot to defeat me. We’re not going to be so easily defeated. And so then the squirrel could kind of relax a bit. And the squirrel’s very fast and it jumps to decisions. So it has this, it has this alacrity, it has this like energy to it. And it would be really nice if it could be more energetic and carefree and less like squirrelly, you know, less like sort of like scurrying here and there in the darkness or in fear. So that’s its wish.

P: Received. The Furry Friend’s secret wish is for a champion, a protector for its hopes and dreams, so it could relax, be more energetic and carefree rather than anxious and fear-driven. It wishes for a stronger assurance that it will not be easily defeated.

The Practice Partner has gathered all the information it needs for the session, so now it simply reflects back what it’s hearing.

N: Yeah, that’s right. And I’d like to end this session, but just make sure enough of the information is there. And before we end the session, I also just want to acknowledge this part for the work that it does and also acknowledge that there’s more to learn about who’s holding these wishes, these dreams. So I’d like to just make a note of that for next time. And maybe to some extent, the squirrel is protecting that little boy who has all these dreams and wishes and is very tender. So I get the sense that as we engage with the furry friend today, that there was simultaneously a protector and an exile. I could feel the vulnerability, but I could also feel this scurrying on top of that vulnerability. So I get the sense that this furry friend is a protector. And so I just want to thank it for the work it does and make a commitment to continue this work and understand all the parts that are involved.

Nick acknowledges the part and makes a commitment to do more work, which is a common practice in IFS.

P: Acknowledged. I have stored that information. The Furry Friend, while holding a protective role, is also associated with an underlying vulnerability that might be linked to the Little Boy part. There is more to explore about this dynamic in future sessions. Here is the updated information about all the parts:

{

"name": "Furry Friend",

"emotional_feeling": "Fear, anxiety",

"appearance": "A little furry animal clutching an acorn",

"bodily_sensation": {

"feeling": "Anxiety in chest, shortness of breath"

},

"speech": "Don't take this away from me.",

"job": "Hide, hoard, and protect hopes and dreams to prevent disappointment",

"fear": "Hopes and dreams, and potentially you, will be destroyed",

"belief": "You are defined by your aspirations and these can be easily destroyed",

"wish": "For a champion, a protector for its hopes and dreams, so it can relax and be less fear-driven"

}

Nick decides to end the session. The Practice Partner generates structured data that summarizes the essential qualities of the part. This data is saved across sessions, so in a future session Nick can do further work on this part, or learn how it relates to other parts.

Benefits of the Practice Partner #

As of writing this I have logged 20 sessions with the AI Practice Partner. I’ve also observed four volunteers – recruited from IFS Facebook groups – conduct their own sessions. These volunteers bring a diversity of experience with IFS: one is an IFS-informed licensed therapist, another is an IFS-trained coach, another is a coach who is new to IFS, and the least-experienced described themselves as “IFS-curious.”

Based on the feedback from these volunteers, alongside my own observations, the Practice Partner has a few advantages over other self-therapy tools:

It structures unstructured thought. The Practice Partner is designed to receive and help process raw emotional input. There is no mental state for the individual that would be too messy for it to work with. It then turns around that input as structured data, faithfully filling out information about parts on behalf of the client. As one tester said after it succinctly summarized his inner monologue, “My God, it filtered out my fluff!” This is an area where the Practice Partner shines, allowing it to quickly build trust with the individual: “I feel more comfortable knowing how this works now, knowing that I can just kind of ‘blah’ out all of my junk and it’ll just pick up the relevant pieces.”

It educates. The Practice Partner assumes the individual already has a strong IFS background. So there’s no educational or explanatory material. That said, whenever volunteers were stuck, it was natural for them to ask the Practice Partner for help. For example, when one tester expressed annoyance with a part, it encouraged them to unblend, as the system prompt instructed it to do. But when the tester asked for tips to unblend, the Practice Partner provided this unscripted answer (which will be better formatted in future versions):

Try these steps: 1. Recognize you are blended with a part. You’ve done this by acknowledging annoyance. 2. Ask the part to separate from you. Internal dialogue might be: ‘I know you are there, and I’d like to understand you better. Can you step back just a little?’ 3. Use visualization. Imagine the part moving away from you, leaving you at the center. 4. Check in with your feelings. After attempting to unblend, see how you feel towards the part now. Try this and then share how you feel towards the part.

It takes feedback. I’ve tuned the Practice Partner to my own preferences over the course of several sessions, such that it now suits me quite well. To some extent, that same tuning is available to individuals, even if they don’t have a way to edit the system prompt directly. One tester, feeling a bit overwhelmed by the multi-part questions the Practice Partner kept posing, asked “Can we please do these one at a time?” It immediately complied, changing its approach for the duration of the session. Other corrective feedback works just as well; an individual can spontaneously switch between parts, or change the name of a previous part, and the tool adjusts seamlessly.

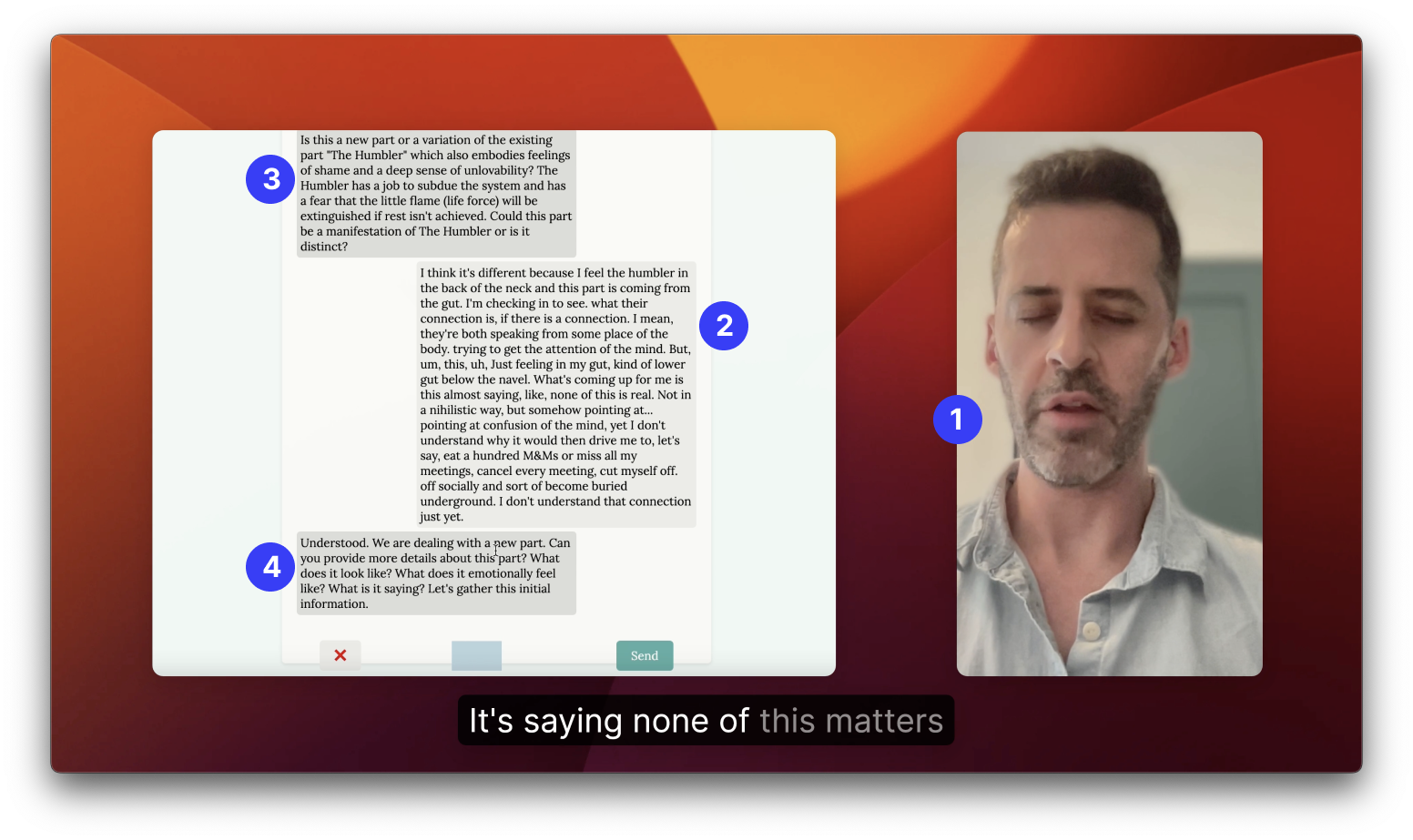

It draws connections. The more one uses it, the more useful the Practice Partner becomes. This virtuous cycle has to do with the way that the system structures and represents data. To make this concrete, here is an exchange from a recent session:

Nick: Okay. Just settling in and contacting feelings in my belly. There’s kind of a lot of shame circling around, and yesterday I sort of just had this throwaway day that…had me connecting with really low feelings for the first time in a while… Today I’m feeling better, but yeah almost that feeling of like wanting to be underground and eating and numbing and consuming as a way of kind of like… burial, burial under sensory experience.

Practice Partner: Is this a new part or a variation of the existing part “The Humbler” which also embodies feelings of shame and a deep sense of unlovability? The Humbler has a job to subdue the system and has a fear that the little flame (life force) will be extinguished if rest isn’t achieved. Could this part be a manifestation of The Humbler or is it distinct?

N: I think it’s different because I feel the humbler in the back of the neck and this part is coming from the gut. I’m checking in to see what their connection is, if there is a connection.

Even though I concluded these feelings were coming from another part, the question was incredibly perceptive. It was the kind of question that only a very engaged therapist or close friend would be in a position to ask.

These are promising early results. If these benefits hold for most new users, I expect the Practice Partner will increase the likelihood of an individual establishing and maintaining a self-therapy practice. From there, the practice itself will open doors to self-discovery, healing, and transformation.

That has been the case for me.

Limitations to the Practice Partner #

As a prototype, the AI Practice Partner I’ve built currently has many limitations. To name a few for the technically inclined: it has poor error handling; it sometimes “hallucinates” speech when the individual is not speaking; it is slow; it doesn’t format responses; it doesn’t have a way to maintain context over long sessions; it is not secure or HIPAA compliant. All of these are reasonably straightforward to address.

The Gloria Films, recorded in 1965 and still used in therapist trainings today, offer a glimpse into the nuance of the therapeutic container.

But the Practice Partner also has some deeper problems. One may be the conversational medium itself. The mere presence of a conversational interface, with familiar chat bubbles and a “Send” button, may subtly direct the individual toward back-and-forth exchanges at the expense of deeper work. One tester, an experienced IFS therapist, conducted a 20 minute session without once consulting the Practice Partner for feedback. All the same she went quite deep in her session, weeping with compassion for her wounded parts. This was a wonderful reminder that fundamentally, doing IFS with a partner is not about having a conversation. It’s about creating a therapeutic container.

The Gloria Films, recorded in 1965 and still used in therapist trainings today, offer a glimpse into the nuance of the therapeutic container.

But the Practice Partner also has some deeper problems. One may be the conversational medium itself. The mere presence of a conversational interface, with familiar chat bubbles and a “Send” button, may subtly direct the individual toward back-and-forth exchanges at the expense of deeper work. One tester, an experienced IFS therapist, conducted a 20 minute session without once consulting the Practice Partner for feedback. All the same she went quite deep in her session, weeping with compassion for her wounded parts. This was a wonderful reminder that fundamentally, doing IFS with a partner is not about having a conversation. It’s about creating a therapeutic container.

Testers almost always attempted to respond to whatever questions the Practice Partner asked. I noticed that when it offered up multi-part questions, testers tried to answer them all in one go. While the system prompt could be refined to only ask one question at a time, that would be directive in a different way, pointing the individual down a particular direction instead of opening up many.

Another limitation of the Practice Partner is intentional: it is not trained to assist in the unburdening of exiles, in which another person’s healing energy can be indispensable. As a result, the system is currently only able to deploy a subset of the IFS playbook, and can’t help much with the deeper protocols.

Future directions #

Despite its limitations, the AI Practice Partner shows promise in helping motivated individuals establish a regular self-therapy practice. With additional investment, there is an opportunity to improve the quality of that practice so that more people can go deeper and experience more healing.

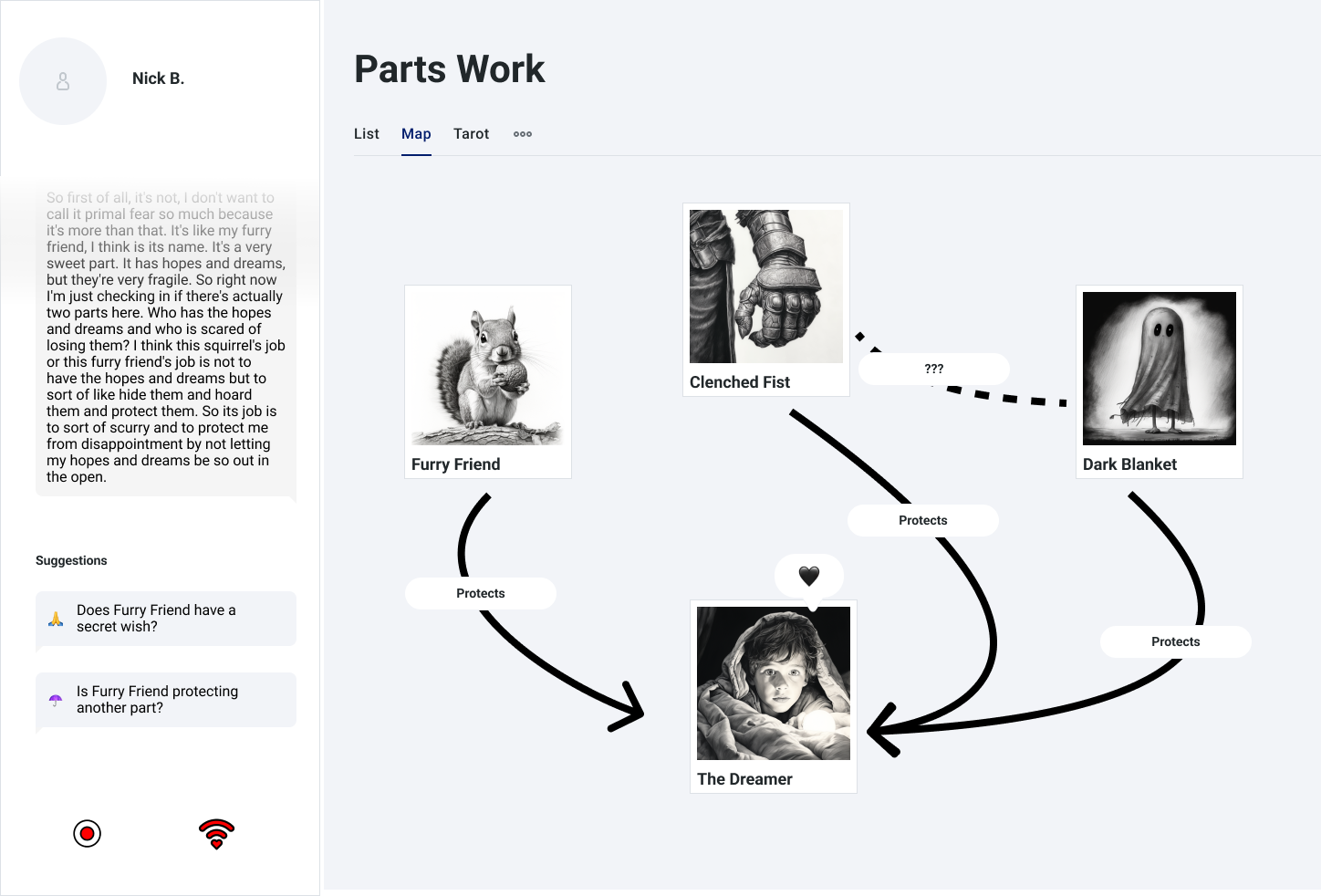

One way to do that is with a digital parts map. The parts map is a popular tool among IFS practitioners. In the Self-Therapy Workbook, Bonnie Weiss writes:

Many people find it very helpful to map their parts. Mapping can clarify relationships between parts, flesh out the number of parts at a trailhead, illuminate the protective system, illustrate which parts are central to the system and which are peripheral, show where parts stand in terms of their relationship to the Self, and much more.

Mapping can be done when you are just beginning to get to know your system. You can check in periodically with the original map to see how things have changed as you keep working. You can also use parts mapping as an ongoing tool for visually tracking your internal work and deciding where to focus your attention.

There are many ways to map your system. One way is to use a large sheet of paper and write down the names or images of the parts as you know them. You can draw lines or arrows to illustrate the relationships.

Here, the benefit of structured data over static worksheets becomes apparent. With a little engineering effort, the Practice Partner could automatically generate a parts map from the data, illustrating parts and their relationships on a canvas in realtime. This would provide individuals with a synoptic view of their inner system, along with the ability to dive into individual parts.

Once again, AI technology may have a useful role to play here. I myself have a very limited visual imagination – it’s hard for me to picture anything in my mind’s eye. So I turned to Midjourney, an AI-powered image generation tool, to illustrate my parts. As with ChatGPT, the prompt plays a crucial role in Midjourney; to find an evocative style inspired by the book, I landed on this:

black and white pencil sketch of {part description}, dreamlike illustration, harsh realism, storybook illustration, emphasizes emotion over realism, nightmare, detailed sketches

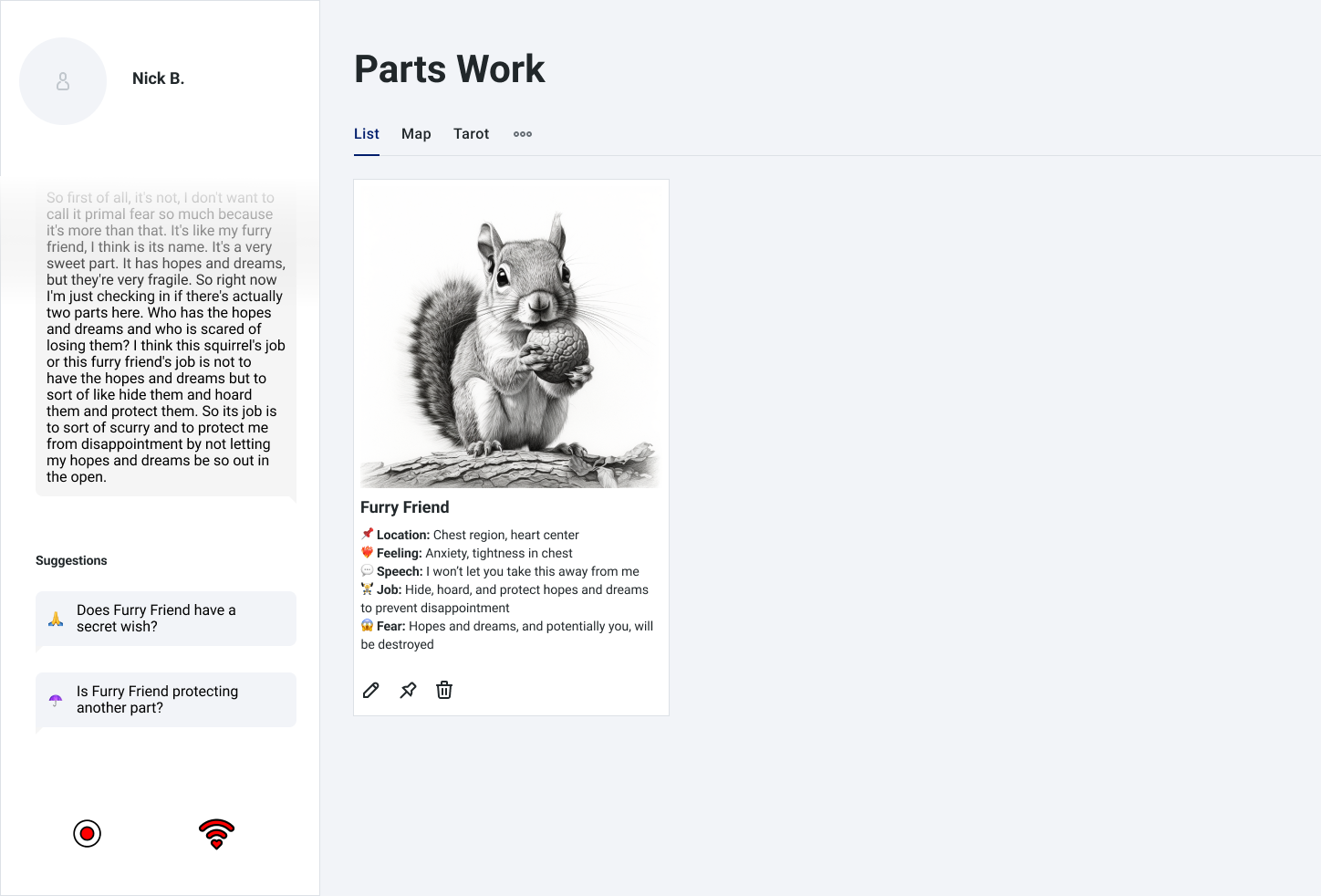

That produced visualizations for parts like Young Dreamer, Furry Friend, Dark Blanket, and Clenched Fist, seen here:

For now, I maintain my parts map in the design tool Figma, separate from the AI Practice Partner. But a more fully realized version could complement the conversational interface with an interactive visualization of the parts. This would create what Jeffrey Heer calls a “shared representation” of the data; a canvas on which both the system and the individual can work in tandem.

Below is a wireframe that reimagines the transcribed session that we covered earlier.

The visualization would reduce the pressure on the conversational medium to do reflection. It could simply transcribe the individual’s words, convey ambient information like a “Self-energy strength signal,” and offer unobtrusive suggestions on what to explore next:

The canvas would update in realtime as the individual uncovers more information about the part, as I do below. As I learn more about this primal fear, I add more information, like the job it has and its fears around not doing that job. I also come to know it by a new name and appearance.

In this vision, the conversational interface recedes from the user experience, creating more of a “single-player” feel. One can imagine introducing gamelike elements from cozy sims like Harvest Moon. The parts map itself could nudge the individual to revisit Exiles that haven’t been worked on for some time, or to explore the relationship between Protectors that might not know about each other yet.

Of course, this is just one direction. Given the wide variety of approaches people take when it comes to their inner work, there are many other directions that the design could take.

The design choices that we make in the emerging AI era could have enormous consequences. AI is quickly entering many aspects of our lives, and we currently lack toolkits and design patterns that ensure these systems are implemented effectively and safely. When it comes to mental health, we might ask questions such as: is the system designed to heal us, or to help us heal ourselves? Will it prepare us for the messiness of being human, or will it shield us from that messiness? Will we become more resilient thanks to this system, or more reliant on it?

IFS may be uniquely well-suited for the AI age that is rapidly unfolding. Because IFS has explicit protocols, an AI Practice Partner can be effectively trained to facilitate self-therapy. And its role is narrowly scoped: it should only act in ways that help the individual access their own Self-energy. A well-designed AI Practice Partner may help more people establish a regular practice on their own, between or instead of sessions with a therapist.

My hope is to partner with clinicians, technologists, and research organizations to develop these ideas further within a pilot program. Those interested in supporting this work or exploring a collaboration can email me at nsbarr [at] gmail [dot] com. IFS practitioners interested in trying out the prototype can request access here [NB: The prototype is no longer being maintained, please refer to the prompt text to try it on your favorite LLM.]

Acknowledgements #

Conversations with many people shaped this work. My thanks to William Gan, Jacob Greif, Thomas Howell, Ken McLeod, Natalie Rothfels, Angela Russek, Jennifer Speakman, and Tereza Sukopova.

Thanks to Andy Matuschak for guidance on the work and for helpful comments on an early draft.

Thanks to Kevin Simler for much-needed encouragement and feedback throughout the process.

The acknowledgement of these individuals is not an indication of their endorsement.